Of divine forms

TEXT & PHOTOGRAPHS BY BENOY K. BEHL

| During the rule of the Kushanas, there was a new focus

in art: the depiction of personalities. |

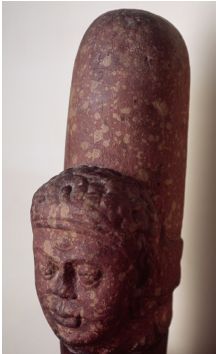

Buddha head, Kushana period (Government Museum, Mathura).

A gentle and smiling expression marks many Buddha depictions

of this period

THE early art of India embodies deep philosophic concepts.

It takes us on a journey through the development of man's

spiritual thoughts: on a path that seeks the goal o

Beyond the sculpted gateways and railings, beyond

the great entrances of the rock-cut caves, beyond the

surrounding walls of the temples lies the most sophisticated

presentation of the philosophic truth. Here is that

which takes our attention away from the multiplicity

of the forms of the world to the concept of the formless

eternal.

From early times and continuing to this day, in the

mountain regions, stupas are often made by

placing a few pebbles one on top of another. As divinity

is seen in the whole of creation, it is the focus of

our attention upon it that creates an object of worship.

All that there is, is a manifestation of the formless

eternal, and we may see that Truth in any object that

we choose to.

The Buddha, Kushana period, 2nd century A.D., Katra

mound Mathura region (Government Museum, Mathura).

The quality of prana, or inner breath, is evident

in the figure. The quality of animation and life marks

this figure as a masterpiece of Kushana period art.

It was donated by Amoha-Asi, a nun, "for the welfare

and happiness of all sentient beings". This is a common

wish expressed in donative inscriptions at Naga, Jaina

and Buddhist sites of this period.

The followers of the Buddha enshrined his mortal

remains in a number of stupas. Thus began

a tradition that spread to many countries. Later

stupas housed the remains of other great

teachers, their personal belongings and also Buddhist

teachings. Numerous stupas were made in

the Buddhist and Jaina traditions in India for many

centuries. Similarly, there is the marvellous philosophic

concept embodied in the Siva Linga.

The Linga is the mark(with a secondary meaning

as a phallic representation) of the formless eternal

taking on the forms of the world. A great and complex

thought process is marvellously encapsulated in

one of the greatest symbols of the world. For instance,

the great Siva Linga of Tamil Nadu, the Aakasha

Lingam of the Chidambaram temple. There is a curtain

in front of it representing the veils of our illusions.

When we move this aside, there is nothing to be

seen beyond: that is the greatest Siva Linga. Tradition

is still alive in the temple which holds that this

is the finest representation of the Upanishadic

Truth.

In early Indian shrines from the 2nd century

B.C. onwards, the focus was on meditation. The aim

was release from the cycle of the pain of life.

The eternal themes were represented in art, and

personalities were not shown. Generalised depictions

of men and women were seen along with the natural

world. Yakshas and Yakshis embodying

the creative force of nature were a favourite subject.

The first formalised deity, seen from the 2nd century

B.C. onwards, was Lakshmi being lustrated by elephants.

In the meantime, the Buddha, or the Enlightened

One, was alluded to by symbols of his achievement

and of his presence.

The Buddha, Kushana period, 2nd century

A.D., Peshawar Valley, Pakistan (National Museum,

New Delhi). The Gandhara art of the Peshawar Valley

is known for some of the finest sculptures made

in dark grey schist. This statue is typically

Gandharan in style with its long, flowing drapery

with heavy schematic folds.

Forms of the world were presented on railings

and gateways as well as on the exteriors of

rock-cut caves. With the passage of time, forms

of the life of the world were also brought into

the interior of the hall of meditation. However,

in the heart of the shrine, there were no forms.

The gentleness of the figures one passed on

the way to the shrine prepared one, until finally

one could meditate upon that which was formless

and beyond the world of forms, beyond desire

and pain.

In the north, Mathura was strategically placed

at the entrance to the plains of the river Ganga.

Thus, it was a major junction for trade. It

was also a great centre of culture and art.

Under the Kushanas, who ruled from the 1st to

the 3rd century A.D., Mathura became the winter

capital of the empire.

Gandharan representation of the

Mahaparinirvana, Kushana period, Gandhara

region ( Indian Museum, Kolkata). Whereas

earlier art had focussed on the purely spiritual

and philosophic aspects of the message, attention

in Gandhara was more on the life of the Buddha

as a heroic individual. Gandharan representations

are full of the drama of his life story, as

in this depiction of the pathos of the moment

of his passing away. Only the monk Subhadra

is seen peaceful as he is aware of the transitory

nature of all life.

The Kushanas, or the Yeuh-Chih, were

tribes who came from southern China. They

patronised Buddhism and the Brahmanas, as

Indian kings had done before them. However,

theirs was a different vision.

The subject of art in India was eternal

themes, not transient personalities. Trees

and flowers, birds and animals, mythical

creatures, common people, creatures that

combined these different beings, all these

were preented in art. So were Yakshas

and Yakshis, who personified the

spirit and abundance of nature.

Bhikshu Bala's Bodhisattva, Kushana

period, Sarnath (ASI Museum, Sarnath).

The early Buddha and Bodhisattva figures

were based upon the Yakshas of the previous

periods. They are impressive in their

monumentality and frontal formality

Another portrait statue has a similar

inscription, this time bestowing royal

and divine titles upon Emperor Kanishka.

He is dressed as a Scythian, with

padded boots and heavy clothes. The

clothing is not in the Indian style,

where it reveals the body shape.

The cult of the worship of kings

did not last beyond the rule of the

Kushanas. However, in this period

there was a new focus: the depiction

of personalities in art. Images of

Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, Jaina tirthankaras,

Siva, Vishnu, Kartikeya an other Hindu

deities were created. These followed

the earlier models of the Yakshas

and N agas.

Queen Maaa's dream (Indian Museum,

Kolkata). In the Gandhara region,

with Greek and other influences,

the focus of art changed in the

Kushana period. Events in the Buddha's

life and depictions of him became

the main subject of art.

Kushana coins present some

of the earliest images of the

Buddha. A Kushana coin also carries

a very early image of Siva, with

his characteristic trident and

with Nandi, the bull who accompanies

him. From the 2nd century B.C.,

there were two Jaina stupas

at Kankali Tila, near Mathura.

Sculpted remains have been found,

which show the close similarity

between the art and symbols of

the Buddhist and Jaina faiths.

Th region also had flourishing

temples dedicated to Naga deities.

An imposing image, over eight

feet (2.44 metres) tall and inscribed

as a Bodhisattva, was installed

at Sravasti around A.D. 100. It

was donated by a bhikshu,

or monk, named Bala. The standing

Bodhisattvas, or Buddhas, carry

forward the formal frontality

of earlier Yaksha figures,

which emphasises their monumentality.

The body displays the softness

of human flesh, unlike muscular

and athletic depictions. A cloth

goes across the left shoulder

and hangs over the arm in very

fine pleats.

Ek Mukhi Siva Linga, Kushana

period (Government Museum, Lucknow).

The Siva Linga is one of the

most profound symbols of humankind.

It is the "mark" of the unmanifest

eternal manifesting itself in

innumerable forms of the world.

Simultaneously, it embodies

the vital forces of nature in

the manifest world.

The form in which the Buddha

was presented was that of

an enlightened being, one

out of many, with 32 attributes

that identified him as such.

The long arms and elongated

ear lobes; the urna,

a mark on the forehead; and

the ushnisha on the

top of the head are some of

the auspicious marks.

A number of images of seated

Buddhas and Bodhisattvas have

been found, including a fine

one from the Katra mound.

This was donated by Amoha-Asi,

a nun, “for the welfare

and happiness of all sentient

beings”. This is a common

wish expressed in donative

inscriptions at Naga, Jaina

and Buddhist sites of this

period. The quality of prana,

or inner breath, is evident

in the figure. There is a

quality of animation and life

that marks this figure as

a masterpiece of the Kushana

period art. Behind his head

is a large halo with scalloped

edges, representing the emanation

of light.

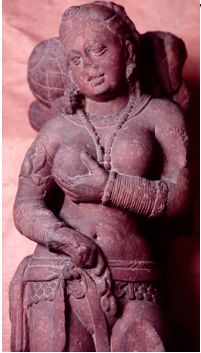

LAKSHMI, KUSHANA PERIOD,

Mathura region (National

Museum, New Delhi). The

earliest formalised deity

seen everywhere in Indian

art is Lakshmi. She embodies

the abundant fruitfulness

and bounty of nature

An image of Surya,

who represents the sun,

was found at Kankali Tila.

The image was also made

in the 2nd century B.C.,

in a vihara at

Bhaja in western India.

The boots, jacket and

moustache indicate Iranian

influences.

An architectural fragment

from Mathura shows an

image of a Siva Linga

being worshipped. Several

lingas of this period,

with one face or with

four faces, have been

found. Kartikeya is also

depicted, carrying a spear.

He was later incorporated

into the Hindu pantheon

as the son of Siva.

stupa, the Yakshis

and the trees that they

stand against or grasp represent

nature. It must be remembered

that in Indian thought all

beings, human, animal and

plant, are intrinsically

the same. This kinship of

life is perfectly expressed

in these images, where the

touch of a maiden brings

trees to blossom.

Yakshi with fruit and

urn, Kushana period, from

a stupa railing pillar

(Government Museum, Mathura).

Images of the natural

world met the devotee

as he circumabulated the

stupa

Buddhism reached

Peshawar, in the Gandhara

region, in the 3rd century

B.C. through the emissaries

sent by Emperor Asoka.

This region was a meeting

point of the cultures

that travelled on the

trade routes from China

to the Mediterranean.

Concepts of Indian philosophy,

which placed emphasis

on the renunciation

of worldly desires,

were new to many here.

Kanishka held the

Fourth Great Buddhist

Council in Kashmir.

This was the first time

that Mahayana Buddhism

was given the full support

of royal patronage.

The council was also

significant for making

Sanskrit the main vehicle

for Buddhist scriptures.

The Mahayana school

of thought, which was

far less austere than

the earlier Buddhism,

soon gained popularity

in the Gandhara region

as well as in Central

Asia and China.

Vrikshadevi, Kushana

period, Jaina stupa

railing, Kankali Tila

(Government Museum,

Lucknow). The vitality

and exuberance of

nature is beautifully

expressed in all monuments

of this period that

survived in north

India as well as in

the rock-cut caves

of western India,

such as at Karle

Little remains

of the numerous

Buddhist monuments

that were made in

Kushana times in

the Gandhara region.

However, vast numbers

of the sculptures

of this period have

survived. The stone

these were made

from is the local

grey schist. The

sculptures of this

region show influences

of Mediterranean

and Persian styles.

Instead of the spiritual,

idealised forms

of Indic mainstream

tradition, these

sculptures attempt

to present the appearance

of people in the

world and their

everyday expressions.

The drapery shows

the influence of

Western models.

Whereas in the Mathura

school the figures

are presented in

transparent, light

clothing, here the

garments are made

with heavy folds

and great emphasis

is given to their

plasticity. The

body is more muscular,

in keeping with

Greek and Roman

norms.

Depiction

of torana,

or gateway,

of stupa,

a fragment

of a Jaina

stupa railing,

Kankali Tila,

near Mathura

(Government

Museum, Lucknow).

In ancient

times, the

symbols and

motifs of

the art of

all faiths

in India were

the same.

This depiction

is identical

to the toranas

of Buddhist

stupas of

early times

The worship

of the stupa

continued

in Gandhara.

However,

the stupa

was considerably

smaller

and was

surrounded

by rows

of image

shrines.

These contained

images of

Buddhas

and Bodhisattvas,

and their

large numbers

indicate

the shift

in the emphasis

of worship.

Unlike Gautama

Buddha,

who is beyond

worldly

adornments,

Bodhisattvas

were adorned

with jewellery.

Beyond

the world

of forms,

the stupa

had earlier

been kept

plain. Now,

narrative

panels relating

the life

of the Buddha

were placed

on it, at

the base.

The Four

Great Events

in the Buddha’s

life were

presented

most often.

Other incidents

and legends

from his

life were

also introduced.

Here, the

emphasis

became more

on the drama

of life

in the ephemeral

world. Human

life, personified

in the Buddha,

before and

after enlightenment,

became the

vehicle

of the message.

Depictions

in the Gandhara

region significantly

dramatised

the events

of the Buddha’s

life and

presented

them with

charged

emotions.

Woman's

Shringhar,

Kushana

period,

scene

on a pillar

railing

(Government

Museum,

Mathura).

The grace

and delicacy

of the

human

form is

sensitively

expressed

in this

scene,

which

meets

the worshipper's

eye as

he goes

around

the stupa

The

first

of the

Four

Great

Events

to be

presented

in the

narrative

sequences

that

were

created

was

the

birth

of the

Buddha.

Here,

Queen

Maya

is made

in the

continuing

tradition

of Yakshis,

who

stand

beneath

trees.

The

name

Maya

means

“the

illusory

nature”

of the

world

of forms

and

is there

as a

constant

reminder

for

us.

At

the

event

of his

enlightenment,

the

Buddha

is depicted

as meditating

under

a pipal

tree.

Mara,

which

means

“to

kill”,

represents

the

turbulence

of desires

within

us.

Mara

and

his

army

are

shown

attacking

the

Buddha

with

a variety

of weapons.

The

Buddha

remains

serene.

The

first

sermon

is depicted

with

deer

to indicate

the

location

at the

deer

park

at Sarnath.

The

final

Great

Event

is the

Parinirvana

of the

Buddha,

when

he leaves

behind

the

pains

and

shackles

of his

earthly

body.

The

expressions

of grief

of his

followers

are

dramatic.

Only

one,

the

monk

Subhadra,

is peaceful

as he

is aware

of the

transitory

nature

of all

life.

Naga

Deities,

Kushana

period,

horizontal

beam

(Government

Museum,

Mathura).

Nagas

are

among

the

earliest

deities

to

be

depicted.

They

are

seen

in

the

art

of

all

religious

faiths.

One

of

the

most

dramatic

contributions

of

the

Gandhara

region

to

Buddhist

art

is

the

depiction

of

Siddhartha

during

his

period

of

extreme

asceticism.

This

depiction

shows

the

Buddha

severely

emaciated,

with

bones

and

veins

sticking

out.

It

is

an

exaggerated

presentation

of

dramatic

proportions.

The

narrative

depictions

and

figures

in

the

art

of

Gandhara

were

formulated

by

the

end

of

the

1st

century

A.D

The

sculpture

flourished

at

its

best

in

the

2nd

and

3rd

centuries.

The

production

of

the

Buddhist

art

of

Gandhara

came

to

an

abrupt

end

in

the

5th

century

with

the

invasion

of

the

Huns.

In

the

meantime,

the

tradition

of

art

in

the

northern

plains

of

India

continued

to

evolve.

Mathura

continued

as

a

vital

centre

of

art.

The

sculptures

made

there

have

been

found

far

and

wide.

This

is

noteworthy,

as

in

this

period,

it

was

the

sculptors

who

were

usually

known

to

travel

and

not

the

artworks,

which

were

made

in

heavy

stone.

These

were

obviously

used

as

models

for

the

art

of

other

regions.

Vishnu,

Kushana

period

(Government

Museum,

Mathura).

In

this

period,

forms

were

created

of

the

many

deities

of

the

Indic

traditions.

These

became

pan-Indian

representations

of

philosophic

ideas

and

concepts

that

continue

to

present

times.

The

portrayal

of

deities

had

become

central

to

Indian

art.

These

deities

were

the

personifications

of

qualities.

By

meditating

upon

them,

one

can

awaken

the

best

that

is

within

one.

This

concept

of

deities

travelled

from

India

to

other

countries

of

Asia.

It

took

deep

root

everywhere,

and

to

this

day

the

puja,

or

the

adoration

of

deities,

continues

in

these

lands.

These

graceful

representations

move

and

transport

us

far

from

worldly

concerns

to

a

peaceful

realm

within.

They

are

a

path

to

take

us

eventually

to

a

realisation

of

the

formless

eternal.

|

|