Indian

paintings in Sydney

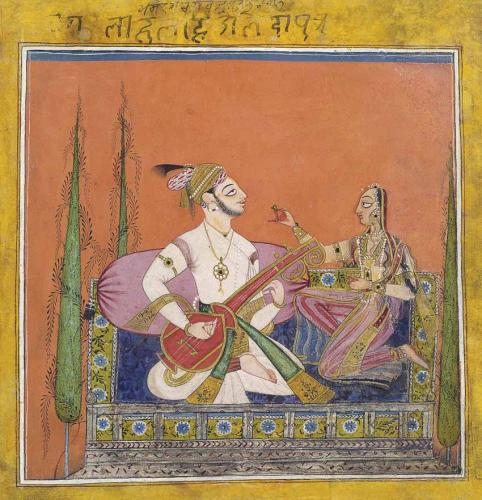

RAGAPUTRA VELAVALA OR BHAIRAVA, circa 1710, opaque watercolour

with gold on paper, Punjab Hills, Basohli. All images Art

Gallery of New South Wales Collection except where mentioned.

The lavish palette that is Indian painting reflects the

mingling of many forces on the subcontinent throughout history.

As wave upon wave of conquerors swept across India, the

encounters between victor and vanquished profoundly influenced

the landscape of art. New and different styles of painting

were woven into a native fabric rooted in tradition, caste,

religion and culture. Intimate Encounters: Indian Paintings

from Australian Collections at the Art Gallery of New South

Wales, Sydney, traces the path of Indian painting through

the last 500 years, a legacy of distinct styles. Documenting

the major schools of Indian art are 77 paintings drawn from

the Gallery's own Asian holding and from public and private

collections throughout Australia. Beginning with pre-Mughal

painting of the late Sultanate period, the display explores

the advent of the Mughal miniature. A narrative of its manifold

styles gives expression to the miniature, from inception

to ascendancy and finally to its demise, which changed Indian

art forever.

When

Muslim incursions threatened 11th-century India, they found

an ancient civilisation based on indigenous faiths. Hindu

and Jain manuscript painting from the palm leaf tradition,

greeted the first Islamic dynasties of the Sultanate period

(1192/1206-1526). An archetypal Indian style was flat horizontal

composition patterned with religious icons and motifs in

primary colours. Paper, introduced to Persia from the Silk

Road, had arrived in India by the mid-14th century. The

use of paper and pigments from opaque water-based mineral

and organic dyes encouraged manuscript illustration. The

Kalpasutra, ‘Book of Precepts', circa 1400s, is an

illustrated Jain scripture, containing biographies of 24

jinas, saviour-saints. An early horizontal folio, The 14

Auspicious Dreams of Queen Trishala, enacts the tale of

one jina, Mahavira, arranged in three registers complete

with the auspicious goddess Lakshmi, elephant, bull, chariot

and banner. Indigo blue, red and brown from insect and plant

resins are the dominant colours. As pigments became more

abundant, a decorative style ensued. One of the earliest

surviving illustrations of a 10th-century, Hindu text, the

Bhagavata Purana, circa 1520-1530, is a folio painting.

Vivid colour schemes of red, yellow, blue and green frame

a scene celebrating the Hindu god Vishnu in one of his manifold

forms as the blue-skinned Krishna. It depicts an attempt

on the latter's life, where animated figures in profile,

characterised by black outlined eyes, a chariot and charioteer,

are stark elements of pre-Mughal Hindu painting.

These

principles of Indian art were subsequently transformed.

Following his victory at the Battle of Panipat in 1526,

Babur (r.1526-30), a descendant of Timur, initiated Mughal

rule in India. The synthesis of indigenous Indian and Persian

court traditions brought about an unparalleled evolution

of Islamic art and culture. Hindu epics such as the Ramayana

and the Mahabharatha were translated into Persian, the language

of the Mughal court. Babur, who had a great love of poetry

and literature, initiated the tradition of recording memoirs.

His successors were bibliophiles and continued to import

Muslim manuscripts from Persia, while encouraging manuscript

production in India itself. Delhi emerged a centre of learning

housing scholars and bookmakers of Persian provenance.

The

Mughals then formalised the patronage of art. To embellish

their courts with decorative objects, karkhanas, imperial

workshops, were staffed with master craftsmen from Safavid

Persia (1502-1736) whose ateliers were heavily dependent

on the Timurid artistic tradition. Humayun (r.1530-40, r.1555-56)

who succeeded Babur, retreated to Persia and returned to

India with the talented Persian artisans, Mir Sayyid Ali

and Abd as-Samad. The empire was consolidated by Humayun's

son, the emperor Akbar (r.1556-1605), a great patron of

the arts who built a royal capital, Fatehpur Sikri near

Agra, and established an imperial atelier. The art of manuscript

illustration developed as folios were decorated with miniature

paintings. As opposed to pre-Mughal tradition, they were

projected in the vertical format, reaching new levels of

artistry. Artists produced illustrated manuscripts of the

Persian classics, experimenting with Hindu, Jain and Sultanate

prototypes to create a distinct Mughal style. Narrative

miniatures of Persian ancestry chronicled the emperors'

lives and exploits in and outside of court. The Baburnama,

‘History of Babur', after Akbar's grandfather, and

his own Akbarnama, ‘History of Akbar', circa 1595 -1598,

were exquisite folios or album leaves stored for posterity.

Portraiture was a genre that developed directly from memoirs

and biographies illustrated in this manner. Before the Mughal

conquest, Indian portraiture was not intended to capture

the formal likenesses of its subjects. However even in miniature,

the Mughal portrait was infused with life, taking on the

character of the person painted.

In

time, the miniature incorporated techniques of fore-shortening

and shading for greater depth and realism. Sophisticated

colour techniques, kept secret, were employed by artists

who often had their signatures hidden within the work itself.

The formula for paints, it later transpired, was not only

in the original Persian but also in verse. One of the earliest

miniatures displayed, Jahangir as Prince Salim returning

from a Hunt, circa 1600-1604, is rendered in subtle hues

with a sensitivity to detail. Akbar's son, Salim, the future

emperor Jahangir, ‘Seizer of the World' (r.1605-1627),

is seated on an elephant with two retainers, and presented

with a pair of game, surrounded by a retinue of attendants.

The treatment of this brutal sport strewn with animal carcasses,

is set against a soft undulating landscape, suggesting early

use of perspective.

Mughal

India however continued to be dominated by the Hindu faith.

The cult of Krishna, the eighth reincarnation of Vishnu

was of great spiritual significance. The miniature grew

to integrate episodes from his life. The Lotus-clad Radha

and Krishna, circa 1700-1710, dwells ostensibly on the romance

between Krishna and Radha, the fairest of the gopis, herdswomen.

Both are clothed in white lotus petals from head to foot,

and carry lotus flowers, a symbol of purity. They are but

reincarnations, and the actual allusion is to a union with

the divine. Music was, and remains an intrinsic part of

Indian life. An idealised image of a bejewelled pair in

the Ragaputra Velavala or Bhairava, circa 1710, shows the

man playing a stringed instrument while being offered a

digestive by his lady. Both have large eyes and rounded

chins, and the drawing of stylised trees embody the Basohli

style of the Punjab Hills. Krishna appears again with three

female musicians in a musical mode, the Vasant Ragini, circa

1770, referring to spring, whose fecundity is implied by

a luxuriant grove of flowering trees in glowing colour.

The

miniature painting tradition was not confined to the Mughals.

Even their fiercest opponents eventually succumbed to prevailing

Mughal taste. Originating in Rajasthan in the northwest,

the Rajputs had an established reputation as fearsome warriors.

Dominion of their independent Hindu kingdoms - with the

exception of Mewar (Udaipur) - was achieved by Akbar only

in 1569. The fusion of Mughal and Rajput art created a new

visual and figurative language shaped by the diversions

of the court. Indigenous Rajput figures outlined in black

and filled with opaque colour, coexisted with delicately

painted specimens where detail was given to costume and

ornament of Mughal fashion. Flourishing from the 1650s to

the 1850s, the focus of this genre was poetical and mythological

allegory, expressed in narratives of classical Hindu devotional

cults.

The

Rajput courts of Bikaner, Jaipur, Kotah and Marwar (Jodhpur)

were partial to Mughal type portraiture. Its members, the

Maharana, the highest hereditary ruler as well as the Rajput

nobility were consummate horsemen, to whom the equestrian

portrait had particular appeal. Show of weaponry such as

the kartar, two-handled dagger, the talwar, sword and the

shield, were personal and social indicators of military

prowess. The Portrait of Raja Kesari Singhji of Jodhpur

on Horseback, circa 1830, features the turbaned ruler in

profile, smoking a water pipe on an elaborately bedecked

horse. A lively composition of much movement, he is the

dominant figure, towering over three retainers on foot.

Rajput

court art went on to form panoramic compositions of much

pomp and pageantry. The procession, a show of clan identity,

was venerated. Another genre was the ragamala, ‘garland

of musical modes' style, where colourful pictorial arrangements

evoked music and rhythm. A poem, the Baramasa, ‘Twelve

Months', of sentiments associated with the passing months

was also depicted in the miniature. Only Mewar of the Rajput

principalities resisted Mughal influences. The sheer vigour

of its dizzying style is evident in the Parashurama, circa

1800s, an action-filled episode from one of Vishnu's incarnations.

The killing of a magical cow, able to grant all favours,

results in dismembered limbs, weapons and embattled figures

in a picture of much symbolism, drama and colour.

The

last vestiges of Mughal power saw the advent in India of

the Portuguese, the Dutch and the British. Coloniser and

colonised met in a new encounter. Midway through Akbar's

reign, Jesuits from the Portuguese colony of Goa had brought

him illustrated bibles. This rare insight into European

painting had its elements imperceptibly fused into the miniature,

despite protests from orthodox believers. Akbar's son, Jahangir,

also a connoisseur of art, dealt with the English East India

Company which opened its first trading post at Surat, Gujarat

in 1612. Anxious to secure its place on the subcontinent,

the Company presented the first British oil paintings, including

royal portraits, to Jahangir in 1616. Offering further clues

to western conventions, they were passed on to court artists.

Gradually a ‘realistic' miniature style surfaced employing

subtle European references. Todi Ragini, circa 1720-1857,

is an immaculate late Mughal portrait of the ragini, a solitary

mistress of the musical mode. She stands in profile on a

grassy mound with a vina, classical stringed instrument,

whose musical sounds have attracted two deer. The detail

of her orange ghaghra, gathered skirt, may be Indian but

the horizon is of European persuasion.

The

crumbling empire run by Jahangir's grandson, Aurangzeb (r.1658-1707),

effectively the last Mughal emperor, resurrected Islamic

orthodoxy. He put a halt to imperial patronage of the arts,

forcing local artisans to find new clients. Among them were

the growing British residents, Madras, Bombay and Calcutta

having joined the Company's trading posts by 1700. After

Mughal power collapsed in 1757, the English East India Company

emerged the de facto government of India. The naturalistic

Mughal painting tradition appealed directly to Anglo-Saxon

instincts. Local ‘Company artists' were employed to

make detailed drawings of local flora and fauna specimens.

European engravings and prints found in India introduced

linear perspective whose principles were drafted into new

works. In the process they gave birth to the hybrid Indo-European

school of Company Painting. Indian ‘exotica' portrayed

included native occupations such as Snake Charmer, circa

1780, from Tamil Nadu. While its flat background and primary

colours hark back to pre-Mughal times, the play of light

and shade suggest western ideals. Eventually portraits of

Company sahibs and their families appeared in indoor settings

complete with domestic servants, or outdoors in a landscape

imbued with occasional European touch. The genre had enormous

appeal and the Indian aristocracy, no less, followed suit.

Increasingly the works commissioned grew in size to house

immense background detail, and expanded in scope to include

views of major Indian cities. Meanwhile landmarks of the

Raj were captured in hand-coloured aquatints by travelling

British artists attracted to its architectural sites and

landscapes. The renowned Oriental Sceneries, a six-volume

work of 144 aquatints by Thomas Daniells (1749-1840) and

his nephew, William Daniells (1769-1837), was published

around 1808. These developments gradually eclipsed the Indian

miniature. It had no place in a new age. The introduction

of photography in 1840s India finally sealed its fate, since

its subjects, both portraiture and landscape, had found

a new master.