|

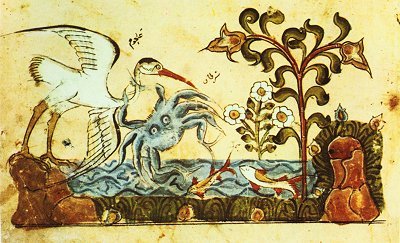

Baghdad, 1300

Illustration from Kalilah wa Dimnah

KALILAH WA-DIMNAH

Book of Indian fables which has been translated into most of

the languages of the Old World. It appears to have been composed

in India, about 300 C.E., as a Brahmin rival to the Buddhist fable-books,

and includes variants of several of the jatakas, or Buddha birth-stories.

It was translated into Pahlavi about 570, and thence traveled

westward through Arabic sources. According to Abraham ibn Ezra,

quoted by Steinschneider ("Z. D. M. G." xxiv. 327),

it was translated directly from the Sanskrit into Arabic by the

Jew (Joseph?) who is said to have brought the Indian numerals

from India. Whether this be true or not, the passage from Arabic

into the European languages was, in each of the three chief channels,

conducted by Jewishscholars. The Greek version was done by Simeon

Seth, a Jewish physician at the Byzantine court in the eleventh

century (see, however, Steinschneider, "Hebr. Uebers."

p. 873, No. 148), and from this were derived the Slavonic and

the Croat versions. The old Spanish version was probably translated

about 1250 by the Jewish translators of Alfonso the Good; this

led to a Latin version. But the chief source of the European versions

of Bidpai was a Hebrew one made by a certain Rabbi Joel, of which

a Latin rendering was made by John of Capua, a converted Jew,

under the title "Directorium Vite Humane"; from this

were derived Spanish, German, Italian, Dutch, and English versions.

In addition to this of Rabbi Joel's, another Hebrew version exists—by

Rabbi Eleazar b. Jacob (1283); both these versions have been edited

by Joseph Derenbourg (Paris, 1881), who issued also an edition

of the "Directorium Vite Humane" (ib. 1887).

It has been claimed that nearly one-tenth of the most popular

European folk-tales are derived from one or other of these translations

of the "Kalilah wa-Dimnah," among them being the story

of Patty and her milk-pail ("La Perrette" in Lafontaine),

from which is derived the proverb, "Do not count your chickens

before they are hatched." Many of the popular beast-tales

and some of the elements of Reynard the Fox also occur in this

Indian book of tales. Much learning has been devoted to the investigation

of the distribution of these tales throughout European folk-literature,

especially by Jewish scholars: by T. Benfey, in the introduction

to his translation of the "Pantchatantra," a later Sanskrit

edition of the "Kalilah wa-Dimnah"; by M. Landau, in

his "Quellen des Decamerone"; by Derenbourg, in his

editions of the Latin and Hebrew texts; and by Steinschneider.

The Hebrew versions are quoted by Zerahiah ha-Yewani, Kalonymus

(in the "Eben Boḥan"), Abraham b.

Solomon, Abraham Bibago, and Isaac ibn Zahula (who wrote his "Meshal

ha-Ḳadmoni" to wean the Jewish public

away from "Kalilah wa-Dimnah").

http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=44&letter=K#ixzz0coY4ylFd

Kalila Wa Dimna

Written by Paul Lunde

Illustrated by Don Thompson

One of the most popular books ever written is the book the Arabs

know as Kalila wa Dimna, a bestseller for almost two thousand

years, and a book still read with pleasure all over the Arab world.

Kalila and Dimna was originally written in Sanskrit, probably

in Kashmir, some time in the fourth century A.D. In Sanskrit it

was called the Panchatantra, or "Five Discourses." It

was written for three young princes who had driven their tutors

to despair and their father to distraction. Afraid to entrust

his kingdom to sons unable to master the most elementary lessons,

the king turned over the problem to his wise wazir, and the wazir

wrote the Panchatantra, which concealed great practical wisdom

in the easily digestible form of animal fables. Six months later

the princes were on the road to wisdom and later ruled judiciously.

Two hundred years after that, a Persian shah sent his personal

physician, Burzoe, to India to find a certain herb rumored to

bestow eternal life upon him who partook of it. Burzoe returned

with a copy of the Panchatantra instead, which he claimed was

just as good as the miraculous herb, for it would bestow great

wisdom on the reader. The shah had Burzoe translate it into Pehlavi,

a form of Old Persian, and liked it so much that he enshrined

the translation in a special room of his palace.

Three hundred years later, after the Muslim conquest of Persia

and the Near East, a Persian convert to Islam named Ibn al-Mukaffa'

chanced upon Burzoe's Pehlavi version and translated it into Arabic

in a style so lucid it is still considered a model of Arabic prose.

Called Kalila and Dimna, after the two jackals who are the main

characters, the book was written mainly for the instruction of

civil servants. It was so entertaining, however, that it proved

popular with all classes, entered the folklore of the Muslim world,

and was carried by the Arabs to Spain. There it was translated

into Old Spanish in the 13th century. In Italy it was one of the

first books to appear after the invention of printing.

Later it was also translated into Greek and then that version

into Latin, Old Church Slavic, German and other languages. The

Arabic version was translated into Ethiopic, Syriac, Persian,

Turkish, Malay, Javanese, Laotian and Siamese. In the 19th century

it was translated into Hindustani, thus completing the circle

begun 1,700 years before in Kashmir.

Not all versions were simple translations. The book was expanded,

abridged, versified, disfigured and enhanced by a seemingly endless

series of translators—to which I now add one more: me. The

story I have selected is not included in the original Sanskrit

version, nor in most Arabic manuscripts of Ibn al-Mukaffa', but

it is of interest because it has entered European folklore as

the story known as "Belling the Cats," which can be

found in the Brothers Grimm and many other places. The difference

is that the Arab mice solve their problem much more subtly than

their western cousins...

'There was once in the land of the Brahmins a swamp called Dawran

that extended in all directions for a distance of a thousand parsangs.

In the middle of the swamp was a city called Aydazinun. The city

enjoyed many natural advantages and its people were prosperous

and could afford to enjoy themselves however they liked. Now there

was a mouse in that city called Mahraz, and he ruled over all

the other mice in the city and in the surrounding countryside.

He had three wazirs to advise him in his affairs.

One day all the wazirs were gathered in the presence of the king

of the mice discussing various things, when the king said: "Do

you think it is possible for us to free ourselves of the hereditary

terror which we and our fathers before us have always felt for

cats? Although we have many comforts and good things in our lives,

our fear of the cats has taken the savor out of everything. I

wish all three of you would give me the benefit of your advice

about how to solve this problem. What do you think we ought to

do?" "My advice," said the first wazir, "is

to collect as many bells as you can, and hang a hell around the

neck of every cat so that we can hear them coming and have time

to hide in our holes."

Then the king turned to the second wazir and said, "What

do you think about your colleague's advice?"

"I think it's lousy," answered the second wazir. "After

we collect all the bells, who do you think is going to dare hang

one around the neck even of the smallest kitten, much less approach

a veteran tomcat? In my opinion, we should emigrate from the city

and dwell in the country for a year until the people of the city

think that they can dispense with the cats who are eating them

out of house and home. Then they'll kick them out, or kill them,

and the ones that escape will scatter in all directions into the

country and become wild and no longer suitable for house cats.

Then we can safely return to the city and live forever without

worrying about cats."

Then the king turned to the third and wisest wazir. "What

do you think about that idea?"

"It's pretty poor," replied the third wazir. "If

we leave the city and go live in the country, how do we know that

the cats will disappear in a single year? And what about the difficulties

we will experience? The wilderness is full of wild animals that

like to eat mice, and they will do us a lot more harm than do

the cats."

"You're right about that," said the king. "So

what do you think we should do?"

"I can think of only one possible plan. The king should

summon all the mice in the city and in the suburbs and order them

to construct a tunnel in the house of the richest man in the city,

and to store up enough food for ten days. Have them make doors

in the tunnel that lead to every room in the house. Then we will

all get inside the tunnel, but we will not touch any of the man's

food. Instead, we will concentrate on damaging his clothes, beds,

and carpets. When he sees the damage, he will say to himself,

`Obviously one cat can't handle all the mice around here! And

he will go get another cat. When he has done that, we will increase

the amount of damage that we do, really tearing his clothes to

pieces. Again he will decide to get another cat. And then we will

increase the damage threefold. That should make him stop and think.

He'll say to himself: "The damage was much less when I only

had one cat. The more cats I get, the more mice there seem to

he.''

So then he will try an experiment. He will get rid of one of

the cats. Immediately, we will lessen the amount of damage that

we do by a third. `That's strange,' the man will say. And he will

get rid of another cat. And we will again decrease the amount

of damage by a third. Then the light will dawn on him. When he

gets rid of the third cat, we will stop our destruction completely.

Then the man will think that he has made a great discovery. He'll

say: `It's not the mice that damage food and clothes, but cats.'

He will run to tell his neighbors, and because he is a rich and

respected man in the town, they will all believe him and throw

their cats out of doors, or kill them, and forever after, whenever

they see a cat, they will chase it and kill it."

So the king followed the advice of the third wazir and before

very long not a cat remained in the city. The people remained

so convinced that they were right about the cats that whenever

they saw a hole in their clothes, they would say, ``A cat must

have gotten into the house last night." And even when there

was an outbreak of disease among men or livestock, they would

say, "A cat must have walked through the town last night."

So by this strategem, the mice freed themselves forevermore from

their hereditary fear of cats.'

Paul Lunde grew up in Saudi Arabia, studied Arabic at the University

of London, and is now studying and free-lancing in Italy.

http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/197204/kalila.wa.dimna.htm

|