Nature

412, 382 (2001) © Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

MARTIN KEMP

Martin

Kemp is in the Department of the History of Art, University

of Oxford, Oxford OX1 2BE, UK.

Maintaining

Masaccio

New

data from the restored 'Trinity' in Florence.

Like

cars and the human body, pictures need regular maintenance.

This is particularly true of wall paintings, even when executed

in the robust medium of fresco, in which the pigments chemically

bond with an upper layer of moist plaster. Murals in publicly

accessible spaces are particularly vulnerable to fluctuations

in environmental conditions and accumulated dirt.

Like

cars and the human body, pictures need regular maintenance.

This is particularly true of wall paintings, even when executed

in the robust medium of fresco, in which the pigments chemically

bond with an upper layer of moist plaster. Murals in publicly

accessible spaces are particularly vulnerable to fluctuations

in environmental conditions and accumulated dirt.

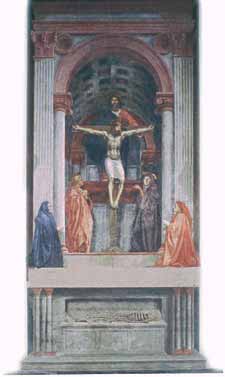

Masaccio's

famous image of the Trinity with the Virgin, St. John,

Donors and a Skeleton has enjoyed a particularly adventurous

history. Painted in the mid-1420s in the church of Santa

Maria Novella in Florence, it was the seminal demonstration

of pictorial perspective in its earliest phase. But the

fresco was totally covered up by an altarpiece 150 years

later, when the interior of the church was completely remodelled.

It was only rediscovered in the mid-nineteenth century,

and its upper section was then transferred to the church's

entrance wall.

It was

finally returned to its original location and reunited with

the battered and fragmentary lower portion containing the

skeleton in 1950, a feat accomplished by Leonetto Tintori.

Large areas of missing paint were restored; almost all the

architectural structures in the lower portion were successively

reconstructed, according to the best intuitions of how the

ensemble originally worked.

Further

work has recently been completed by Cristina Danti and her

team from the Florentine conservation workshop Opificio

delle Pietre Dure to ameliorate the inevitable changes and

deterioration that have occurred over the half-century since

Tintori's painstaking restoration. The Tintori and Danti

campaigns, using traditional and technological means of

examination, have together generated vast amounts of data

about the highly technical optical construction of young

Masaccio's illusionistic spaces (Masaccio died at the age

of 27).

The

key feature is what we now call the 'vanishing point', at

which lines perpendicular to the plane of the picture appear

to converge, and which Masaccio has placed at a reasonable

height for an 'average' spectator. Even with the guidance

of the converging parallels, the construction of the barrel

vault is a far from trivial problem. Examination by Danti's

team reveals that the left side of the curving vault is

criss-crossed with a complex mesh of construction lines,

some of which had been 'snapped' into the wet plaster with

chords (which are pulled out and sharply released to leave

an imprint), and others incised with a pointed instrument

along a straight edge or with some form of compass. Having

used the left side as his elaborate experimental field,

Masaccio completed the right section with a greater economy

of constructional effort.

A geometrical

analysis of Masaccio's painted space — now confirmed

by computer analysis — reveals that he has intuitively

adjusted its regular geometry to make it 'work' as a picture

in terms of its actual site in the nave of the church. Among

the many almost indiscernible subversions of canonical perspective

are the circumferential extensions of the lowest row of

coffers on left and right, presumably to make them appear

to 'sit well' in relation to the arms of the cross. In addition

to such empirical manipulations, the painter has insinuated

some subtle asymmetries into the axial scheme. For example,

God stands slightly off the central axis. We can also see

that Christ's hands overlap the edges of his cross only

on the left.

Although

the prime, frontal viewing position was contrived to coincide

with the width of the side aisle, the viewer entering from

the usual entrance door in the fifteenth century, which

was on the opposite side wall, would have seen Masaccio's

illusion off-centre to his or her left. Masaccio has not

exploited the full effect of parallax — which would

have looked too extreme from other viewpoints — but

he has subtly accommodated the asymmetrical line of approach.

The

collective results arising from the old and new data indicate

how the rules of construction and compositional intuition

operate together in an experimental process that relies

upon a constant interplay between geometry, judgement by

eye, and supreme manual control.